| Main index | Financial Markets index | About author |

Julian D. A. Wiseman

Abstract: Comment on the BoE’s recent description of its implementation of monetary policy, which introduced new stigma, and her failure to rebut a safer alternative.

Publication history: only at www.jdawiseman.com/papers/finmkts/20110518_defence_stigma_zero.html. Usual disclaimer and copyright terms apply.

Contents:

Introduction

(How Monetary Policy Should Be Implemented: A Narrow Passive Corridor);

• The Straw Man

(no money market,

loss of information,

disrupt longer-term money markets,

less incentive to manage liquidity,

banks facing fundamental shocks;

relinquishing control);

• Collateral

(Collateral: A Recommendation,

Eligible Collateral,

The Price of Collateral

(One-week $ Libor and the Fed Funds Target));

• Liquidity insurance;

• Conclusion;

|

• Appendix: The Source of Zero.

This essay is a response to three documents recently published by the Bank of England.

The Bank’s money market framework, by Roger Clews, Chris Salmon and Olaf Weeken of the Bank’s Sterling Markets Division, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin, 2010 Q4.

Recent developments in the sterling monetary framework, speech by Paul Fisher given at the Manchester Economics Seminar, University of Manchester, 30th March 2011.

Central bank policy on collateral, paper by Paul Fisher, 14th April 2011. (Though described as a “paper”, this is in the speeches section of the BoE’s website.)

These three recent papers all have the official imprimatur of the Old Lady. And the first, with multiple authors, seems to have been a significant source for the two of Paul Fisher, who is the BoE’s Executive Director Markets (responsible for policy operations in £ and management of the FX reserves). Hence the three are being treated here together, as an official explanation of the BoE’s actions in implementing £ monetary policy.

Before getting to the BoE’s papers, there should be an explanation of the counter-proposal, a ‘narrow passive corridor’.

The author advocates that each commercial bank should have an overdraft facility with the BoE. For those commercial banks with the largest £-denominated business, this might be ≈ £30bn. For banks with less natural £ business (whether because the banks are smaller, or because their business isn’t £), less. Such overdrafts would be available automatically, one night at a time, against good haircutted collateral, and at a cost of the policy rate. So if a bank finishes the day with a negative balance in the payment system, not more negative than the overdraft facility, it is charged the policy rate with no further fuss. Further, if a bank finishes the day with a positive balance not larger than 25% of the overdraft allowance, this is remunerated at the policy rate less a small spread. This spread might be Max{10bp, 0.02 × Policy}.

Rephrased, in large per-bank size, and massive system-wide size, the BoE would be making a market in overnight money, the price typically being Policy–0.10% / Policy. This two-way price is a ‘corridor’; its automatic application to end-of-day balances makes it ‘passive’; and the typically 10bp spread makes it ‘narrow’.

There are two main differences between this proposal and the family of schemes recently used by the Bank of England.

First, one account versus two.

For each counterparty, the BoE keeps its payment account separate from its overdraft. Commercial banks have a reserve account at the BoE, used for making their own and their customers’ payments. But reserve accounts may not be overdrawn, at least on average. Instead, to borrow, commercial banks must actively take part in an ‘open market operation’, of which there are multiple types. But these operations are either available at a penalty interest rate, or unavailable late in the day, or both. Being able to make payments is essential to a bank, so commercial banks want to be sure of having access to enough money, even if making a payment at short notice. Prior to August 2007 banks could be confident of being able to borrow from each other, so this wasn’t a problem. But since then banks have not been so confident, so have held extra, as a precautionary balance.

The proposal is for ‘one account’, unifying the access to the payment system with the overdraft. And that overdraft is to be available in plentiful size, automatically at the end of the day, at the policy rate rather than a penalty rate.

Second is the unification of all the borrowing types.

Currently there are multiple facilities and operations via which a commercial bank can borrow from the central bank, these being for differing terms, against different sets of collateral, with different certainties of access, and at different prices. Some of these facilities and operations would be suitable for use only by a bank in trouble. And as using a bank-in-trouble facility signals trouble, no bank would wish to use it. In particular, a bank borrowing expensively signals that it cannot borrow cheaply. The BoE has partly fixed this with secrecy—a hidden problem correctly being thought to be less of a problem.

The proposal is for a single borrowing facility, an overdraft facility, as clean and flexible as possible:

Next we come to that which the BoE, and Paul Fisher in particular, choose to rebut.

A … model for implementing monetary policy is the ‘zero corridor’ system. In this case there would be no reserves targets and banks could both lend to and borrow from the Bank in unlimited amounts at Bank Rate every day. Although short term market interest rates should always equal Bank Rate precisely, this system has several drawbacks. First, banks would never need to transact with each other; they simply transact with the central bank via the [Operational Standing Facilities]: there would be little or no commercial overnight interbank money market. That would be unwelcome. For example, the information the Bank deduces from movements in overnight market interest rates would be lost. It might also disrupt functioning of longer-term money markets, given implicit links to the overnight market. Second, if the Bank can always be relied upon to meet daily liquidity needs, then commercial banks have less incentive to actively manage their liquidity. And the Bank would be unable to distinguish between banks using the OSFs to manage their day-to-day liquidity buffers, and those facing more fundamental shocks. Finally, by offering to borrow and lend overnight automatically, the Bank would relinquish day-to-day control over its balance sheet and the degree of risk associated with that.

Things are getting better: the straw men are becoming fairer. In the BoE’s October 2008 consultation, The Development of the Bank of England’s Market Operations, box B(c), the BoE complained that its hypothetical, a zero-width active corridor (rather than a narrow passive corridor) would be too zero, and too active. Well, yes, so it would. So now fast forward to March 2011, and the new hypothetical is a zero-width passive corridor: much nearer.

This paragraph is worthy of examination one clause at a time.

But the BoE complains that with a zero-width corridor (in which the BoE would borrow and lend at the policy rate), “there would be little or no commercial overnight interbank money market”. This is a very important observation, and—the author suspects—at the heart of the BoE’s muddle. Return to the start of a course in economics. What is the purpose of a market? Under various assumptions, mostly true, a market finds the price that maximises the sum of the producer and consumer surpluses. That is, a market makes as large as possible the total of the manufacturers’ profits, plus the total of the amount by which the consumers get it cheaper than it is worth to them. This is an efficient thing for a market to do. But in secured overnight money, the alleged market is there to ‘find’ a price that was chosen by a committee and announced by the central bank. This is not a market in any useful sense; this is a game, and its loss should not be regretted.

Indeed, not only is this not a real or socially useful market, it would not even be eliminated by a narrow corridor, though it would be shrunk. If the BoE were offering to accept deposits at 0.40%, and to lend against heavily haircutted collateral at 0.50%, then one might expect there still to be a market in money at prices above the floor, and depending on how aggressively one-sided is the haircutting, below the policy rate.

Next the worry that “the information the Bank deduces from movements in overnight market interest rates would be lost”. The author has worked in the BoE division that was meant to deduce information from movements in overnight market interest rates. What was then deduced was the poorness of the BoE’s implementation of monetary policy, and little more. For it to be believed that the BoE is really deducing useful actionable things about the real world, this needs much expansion.

Nonetheless, the new system would provide new information. Commercial banks would have an incentive to park lots of collateral at the BoE, thus allowing an overdraft on demand. The central bank would be able to see not just the collateral presently being used, but also a fair part of each bank’s stock of available collateral. This might or might not contain useful information.

Then “It might also disrupt functioning of longer-term money markets, given implicit links to the overnight market”. Well, maybe a little, and also not at all. It would improve supply of, but reduce demand for, longer-term funds secured against eligible collateral.

Supply: bank A lends bank B money for three months. From where does bank A get this money? Perhaps bank A has an excess of deposits that can be on-lent. Or perhaps bank A does not, and borrows this money shorter-term. But if bank A can borrow this more easily and more reliably from the central bank, then that should increase—rather than “disrupt”—bank A’s willingness to lend.

Demand: but why would bank B bother with long-term secured funding? Of course, if bank B did not wish to commit collateral (so wanting unsecured funding), or did not want the central bank’s one-sided haircutting, it would seek term funding in the market. But if bank B has an excess of eligible collateral, then the most convenient course would probably be to park this at the central bank and use the overnight facility, one day at a time. So what? Why would it be bad to incentivise banks to have an excess of eligible collateral, and to park that at the central bank?

The next sentence contains a more subtle error: “if the Bank can always be relied upon to meet daily liquidity needs, then commercial banks have less incentive to actively manage their liquidity”. The proposed narrow passive corridor would change the meaning of “liquidity”, banks no longer managing the old definition, but still managing the new. Money would no longer be the sole definition of liquidity; liquidity would be whatever allowed payments to be made. Eligible collateral would allow payments to be made, up to a large per-bank limit, so the primary focus of liquidity management would be ensuring a sufficient surplus of (haircutted) eligible collateral. Depending on the definitions used, this could be viewed as a harmless “less incentive”, or as a change of focus.

Next comes a comment with sharp teeth: “the Bank would be unable to distinguish between banks using the [Operational Standing Facilities] to manage their day-to-day liquidity buffers, and those facing more fundamental shocks”. This comment alone might change banks’ behaviour. The BoE is saying that banks borrowing at the +25bp corridor bound might be thought to be having problems of the “fundamental shocks” type. Rephrased, stigma at +25bp. Hence banks should try not to use the +25bp standing facilities, for fear of being thought to be in trouble.

This is why it is so important that facilities be stigma-free. If the only way to borrow money is overnight, at the policy rate, then there can be no stigma attached to doing so. If there is a choice, then, when markets are under stress, some banks will feel compelled to choose low-stigma actions, whatever the cost. (After the problem described in The Independent on 31st August 2007—see footnote 8 in the November 2008 letter to Paul Tucker—Barclays’ management banned use of stigma facilities.) Whilst waiting to fix the implementation of monetary policy, a credible means of retracting this stigma-inducing sentence should be found.

The final sentence of the paragraph is an error, presumably careless. “Finally, by offering to borrow and lend overnight automatically, the Bank would relinquish day-to-day control over its balance sheet and the degree of risk associated with that”. But the BoE’s current facilities contain the same relinquishment. Because of the penalty rate and de facto stigmatisation, the facilities might not be used very much, but that control has nonetheless already been relinquished.

For these reasons the arguments against a passive corridor seem weak. Either the BoE should implement a narrow passive corridor, or should better explain why not.

The third of the papers under discussion is about collateral. Again, the critique is prefixed with a recommendation.

The object of monetary policy is to set to the perfect-credit short-term interest rate. This is done with a two-way price. Of course, local-currency deposits at the central bank are perfect credit. Likewise, loans made by the central bank should also be perfect credit, or nearly so. Collateral policy should be based on two objectives: there being enough collateral; and the loans being almost perfect credit.

This is far from some of the BoE’s reasoning about collateral. The different reasoning leads to the same eligibility and haircuts, but to very different pricing.

From 1st July 2011 BoE ‘narrow’ collateral will comprise gilts, other HMT securities, BoE securities, and £, €, $ and C$-denominated securities issued by the governments and central banks of CA, FR, DE, NL and US (source). Given the volatility-determined haircuts, currently and rightly comprising duration and currency components, repo against these is close to perfect credit.

And this is a already lot of collateral. In trillions: UK ≈ £1.0; US ≈ $14.3; DE ≈ €1.8; FR ≈ €1.6; NL ≈ €0.36; CA ≈ C$0.6. After haircuts that totals about £12 trillion of possible collateral. Recall that, pre-QE, the total funding £ need of the banking system was approximately the size of the note issue, now about £52bn, so about 0.4% of the size of the stock of ‘narrow’ collateral.

So far, so good.

The BoE also has a wider set of official collateral: debt in £, €, $ or domestic currency, of the sovereigns and central banks of seventeen other countries and of eleven international institutions, which range from solidly triple-A to being priced for default. The April 2011 Documentation for the Bank of England’s operations under the Sterling Monetary Framework, page 177, says that haircuts of “Corporate bonds and commercial paper issued by non-financial companies … A3/A– or higher” have haircuts of 30% to 42%, depending on maturity, with possible extra haircutting of “portfolios of corporate bonds that are not well diversified, where the largest single bond concentration by market value exceeds 2% of the total market value of corporate bonds delivered”. With that extent of over-collateralisation, this is also almost perfect credit.

So far, so good.

The BoE (after repeated requests) explained more by email:

As noted in the May 2010 Market Notice, the Bank can already apply higher haircuts on a sliding scale basis for collateral with higher liquidity or credit risk. Such higher haircuts are not generally published – indeed in some cases they may be specific to counterparty as well as to the collateral – but are made available to SMF counterparties who have or are considering pledging such collateral. The Bank also reserves the right to apply additional haircuts or amend existing haircuts at its discretion at any time, including on outstanding transactions.

… The Bank’s base haircuts are independent of counterparty, and so do not include a factor for correlation arising from the bank and the underlying assets being from the same country. However, as set out in the documentation, Bank can apply additional haircuts or amend existing haircuts at its discretion at any time, and indeed does do so for wrong-way risk between counterparty and collateral, for example.

This is consistent with the BoE striving for the author’s desideratum of “close to perfect credit”. In particular, collateral of Level D, “own-name securitisations and own-name covered bonds”, is very much “wrong-way risk”, so requiring, and seemingly subject to, very large haircuts.

So the author concurs with the BoE’s judgement about what can be collateral, and the extent to which it should be haircut.

The interest rate at which the BoE lends various with the quality of the collateral, worse collateral attracting a higher interest rate. From Paul Fisher’s paper of 14th April 2011 (and also see ¶3.5(iv) on page 195 of the April 2011 SMF):

the Bank’s prices for lending in its liquidity insurance operations can vary with the liquidity of the collateral delivered and the amount lent, so that use of these facilities only becomes attractive in stressed conditions.

At first glance this seems fair: surely there should be a price penalty to collateral of lower quality? But no: the collateral is of lower quality for a given quantity, but because of the larger haircuts there is more of it: the amounts are not the same. If the haircuts are such that all this monetary-policy lending has near-perfect credit, then quality and quantity are in balance, and all should be at the same price.

And there is a nasty consequence to having such a penalty rate, as explained by this author in Implementing Monetary Policy (when complexity is dangerous, be simple), 30th January 2008:

A CB’s policy rate should be the marginal cost of short-term money against good collateral. But if some counterparties are borrowing at policy+½%, then marginal cost of money has gone up. So just as financial system hits the brakes the central bank hikes rates, by accident as it were. That doesn’t suggest a clean coherent well-thought-through system.

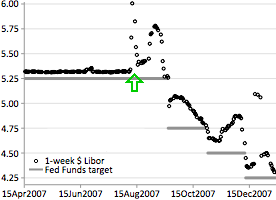

This is just what happened in the US as the credit crisis started: banks resorted to weaker collateral, against which the Federal Reserve charged a higher interest rate. So the system-wide marginal cost of money jumped (chart on right, green arrow). The rules of the Federal Reserve caused a hike in interest rates because the financial system was in trouble! That was unfortunate, but having seen that accident, knowingly to build the same problem into the system must be wrong.

Clews et al construe some of the current facilities as “liquidity insurance”:

A drawback of the zero-corridor system is that it conflates monetary policy implementation and the provision of liquidity insurance. In the corridor and floor systems, usage of the lending facility is exceptional; in the zero-corridor system, by contrast, it is the norm. The lending facility is therefore delivering two objectives, making it harder for the central bank to distinguish between banks that are using it to manage their day-to-day liquidity buffers and those that have experienced a more fundamental liquidity or even solvency shock.

The more the supply of reserves adjusts automatically to accommodate changes in demand, the more seamlessly liquidity insurance is provided. But this makes it more likely, other things being equal, that the banking sector will pursue riskier activities to the detriment of future financial stability.

But lending against collateral of sufficient quantity and quality that the loans are of near-perfect credit is not offering free insurance. When the BoE lends against collateral of short-dated gilts, £98½ is lent against ‘equity’ of £1½. Clews et al do not object to this. But against less secure collateral the BoE might lend only £70 against £30 of equity: this much lower leverage should be less worrisome, rather than more. And, of course, there is a daily mark-to-market, so the owner of the collateral would need more than £30 to withstand a few days of ordinary randomness.

Alternatively, consider a stylised balance sheet of a commercial bank. Each £100 of assets is funded with about £10 of equity and about £90 of borrowing. If all that borrowing is deposits or long-term funding, no market or central-banking borrowing funding would be required. In the opposite case, in which the whole £90 is funded short-term wholesale, an average haircut harsher than 10% would mean insolvency. Such a bank has a very strong incentive to ensure its assets are low-risk, and seen to be low-risk. So a central bank willing to lend 70% of the value of some assets is not providing usable liquidity insurance, whatever that might be.

And this reasoning against a narrow passive corridor is flawed in another way: that reasoning favours bad policy. It implies that the implementation of monetary policy must not work reliably, because otherwise banks might rely on it, which would facilitate banks pursuing “riskier activities”. So to prevent banks relying on the implementation of monetary policy, it must be broken by design, at least a little. And then, when tested under testing conditions, it is ‘discovered’ that it is broken. Really, this philosophy doesn’t work: please abandon it. Choose an implementation of monetary policy that is maximally robust (narrow passive corridor), and that is free of stigma (money is lent only via the upper bound of that corridor).

To conclude, Clews et al with bad news:

… the Bank is minded, in due course, to reinstate substantively those elements of the [sterling monetary framework] that were suspended in March 2009 following the MPC’s decision to embark on a programme of asset purchases

Paul Fisher, with a reason and an excuse:

Until the start of the financial crisis, similar reserves averaging mechanisms were employed at the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan.

Please, no. The two-account multiple-facility multiple-price stigmatised non-overdraft doesn’t work. A narrow passive corridor is more robust, more reliable, and safer. And with a suitable haircutting policy it has no disadvantages. Please, abandon the current central-bank fashion for needless complexity.

| — Julian D. A. Wiseman 18th May 2011 www.jdawiseman.com |

The BoE rebutted a zero-width proposal in 2008 and again in 2011. But this author did not propose a zero-width corridor. For those few readers who might be interested, this appendix traces the source of the zero.

In the 2010 Q4 Quarterly Bulletin is The Bank’s money market framework, by Roger Clews, Chris Salmon and Olaf Weeken of the Bank’s Sterling Markets Division. This says “there is the so-called ‘zero-corridor’ system that has been proposed as a simpler alternative.(1)” That footnote says “(1) See, for example, Buiter (2008) and Wiseman (2007).”

Wiseman (2007), being The pretend market for money, very explicitly describes a non-zero corridor width:

Why not have a zero gap? If there were a zero gap, the size of trades would typically be constrained by the maximum allowable transaction sizes (which are necessary for credit reasons). In general, it is more efficient if a price rather than a quota constrains volume, and these bid/ask spreads of a few basis points suffice to keep finite the desired transaction sizes.

That leaves the reference to Buiter (2008), which is from his FT blog on 25th March 2008, How do the Bank of England and the Monetary Policy Committee Manage Liquidity? Operational and Constitutional Issues.

Some in the Bank of England are very fond of this clumsy, klutzy, over-engineered and pretty ineffective arrangement for money market operations in the overnight sterling market. They remember the bad old days, before the introduction of the current regime on 18 May 2006. That regime was completely incomprehensible. … I am happy to agree that the current arrangement for money market operations in the overnight market in the UK is better than it was before May 2006. It may even be better than the similarly opaque and bizarre procedures of the Fed and the ECB. But it still is a bad arrangement. Fortunately, there is an easy fix.

So far, the Maverecon blog and this author are in agreement.

So when the MPC sets Bank Rate at, say, 5.25%, and if (the inverse of 1 plus) Bank Rate is defined as the price of reserves at the Bank of England, it ought to mean the following:

1. the Bank of England is willing to borrow overnight any amount from eligible banks and building societies at that rate, and

2. the Bank of England is willing, against eligible collateral, to lend overnight any amount to eligible banks and building societies at that rate.

We again can allow for a small bid-ask spread between the Bank of England’s lending rate and borrowing rate to cover transactions costs in the overnight market.

… One consequence of this arrangement might be that banks and building societies would no longer deal with each other in the overnight interbank market, but instead transact only with (and indirectly with each other through) the central bank. …

If this were nevertheless considered an obstacle, the central bank could instead be ready to repo, in the overnight market, any amount against eligible collateral at Bank Rate plus ε>0, and to borrow any amount at Bank Rate minus ε>0, where 2ε is just a bit above a reasonable estimate of the normal bid-ask spread in orderly, competitive markets.

So Willem Buiter seems unstressed by the idea of a zero-width corridor, but is equally happy to concede a narrow corridor. (As an aside, Buiter seems to be recommending an active corridor. Please, no, the corridor must be passive, that is, applied automatically to closing balances without active dealing.)

So of the two alleged sources of a zero-width corridor, one is willing to concede non-zero narrow, and the other is explicitly dis-recommending zero. Zero does not need rebutting.

| Main index | Top | About author |