| Main index | About J. D. A. Wiseman |

Julian D. A. Wiseman

Contents: Introduction, Whether to stop at h=5 t=3, Failure to find a better estimate of the value of the game, Afterword.

Publication history: only here. Usual disclaimer and copyright terms apply.

1. The Chow & Robbins problem asks for the fair value of a game, in which tosses a coin, at least once, until choosing to stop, when one scores the proportion of tosses that are heads. An essay of late 2005, The expected value of sn/n ≈ 0.79295350640…, improved the best known estimate of the value of the game to ≈11½ decimal places. But it did not address any outstanding questions about possible stopping states.

Luis A. Medina & Doron Zeilberger, in ‘An Experimental Mathematics Perspective on the Old, and still Open, Question of When To Stop?’, arXiv:0907.0032v1, ask:

If currently you have five heads and three tails, should you stop?

If you stop, you can definitely collect 5/8 = 0.625, whereas if you keep going, your expected gain is > 0.6235, but no one currently knows to prove that it would not eventually exceeds 5/8 (even though this seems very unlikely, judging by numerical heuristics).

The author provides strong evidence that at h=5 t=4 the value of the game is ≈ 0.580572488…, and hence the value from continuing from h=5 t=3 is the average of this and 6÷9, that average being ≈ 0.623619577, which is significantly less than 0.625. Further, it seems likely that the error in the estimate of EV∞(h=5, t=4) is less than 10−10, so h=5 t=3 really is a stopping state. These further heuristics are consistent with the existing “numerical heuristics” cited by Medina & Zeilberger.

2. The previous code was constrained by memory. Code has been rewritten to remove this constraint. Extending the calculation by a factor of 4 has not improved the accuracy to which the value of the game is known. Current constraints definitely include CPU time, and also perhaps the accuracy of the hardware’s floating-point arithmetic.

With five heads and three tails, should one stop (scoring ⅝ = 0.625), or should one continue? Rephrased, is 0.625 ≥ ½(EV∞(6,3) + EV∞(5,4))? For n as large as has been tested, h=5 t=3 is a stopping state, so it is safe to assume that, with an extra head, so at h=6 t=3, one should definitely stop, there scoring 6/(6+3) = ⅔ ≈ 0.666666. So the question is equivalent to asking whether EV∞(5,4) ≤ 7⁄12 ≈ 0.583333.

The same technique previously used for the value of the whole game can be used to value the game at h=5 t=4. Results are output in the table that follows (new code available from jdawiseman.com/papers/easymath/chow_robbins.c; calculations run on a 1.83 GHz Intel Core 2 Duo processor under Mac OSX 10.6.4 using Xcode 3.2.3).

| i | n = 2i | EVn(h=5, t=4) | Diff EV | Ratio Diff EV | Estimated limit = EV + Diff / (1⁄Ratio − 1) | Diff Estimated limit | Diff Estimated limit × 2i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 32 | 0.576497675084966 | |||||

| 6 | 64 | 0.578233093000500 | 0.001735417916 | ||||

| 7 | 128 | 0.579196754382963 | 0.000963661382 | 0.55529067 | 0.58040003964231 | ||

| 8 | 256 | 0.579752779495916 | 0.000556025113 | 0.57699221 | 0.58051121035538 | 0.000111170713075 | 0.02845970 |

| 9 | 512 | 0.580078876181192 | 0.000326096685 | 0.58647834 | 0.58054136378755 | 0.000030153432162 | 0.01543856 |

| 10 | 1,024 | 0.580274733227757 | 0.000195857047 | 0.60061036 | 0.58056926708142 | 0.000027903293872 | 0.02857297 |

| 11 | 2,048 | 0.580393564822555 | 0.000118831595 | 0.60672617 | 0.58057689315882 | 0.000007626077403 | 0.01561821 |

| 12 | 4,096 | 0.580464868562560 | 0.000071303740 | 0.60004025 | 0.58057184211230 | −0.000005051046521 | −0.02068909 |

| 13 | 8,192 | 0.580507696666527 | 0.000042828104 | 0.60064316 | 0.58057211125895 | 0.000000269146652 | 0.00220485 |

| 14 | 16,384 | 0.580533458617586 | 0.000025761951 | 0.60151977 | 0.58057234717824 | 0.000000235919284 | 0.00386530 |

| 15 | 32,768 | 0.580548981018557 | 0.000015522401 | 0.60253204 | 0.58057251183093 | 0.000000164652695 | 0.00539534 |

| 16 | 65,536 | 0.580558328857386 | 0.000009347839 | 0.60221604 | 0.58057248080675 | −0.000000031024181 | −0.00203320 |

| 17 | 131,072 | 0.580563959800812 | 0.000005630943 | 0.60237917 | 0.58057249044815 | 0.000000009641397 | 0.00126372 |

| 18 | 262,144 | 0.580567350923834 | 0.000003391123 | 0.60222999 | 0.58057248513698 | −0.000000005311168 | −0.00139229 |

| 19 | 524,288 | 0.580569393522691 | 0.000002042599 | 0.60233700 | 0.58057248743098 | 0.000000002293999 | 0.00120272 |

| 20 | 1,048,576 | 0.580570624044048 | 0.000001230521 | 0.60242928 | 0.58057248862324 | 0.000000001192268 | 0.00125018 |

| 21 | 2,097,152 | 0.580571365285460 | 0.000000741241 | 0.60237997 | 0.58057248823938 | −0.000000000383866 | −0.00080503 |

| 22 | 4,194,304 | 0.580571811863659 | 0.000000446578 | 0.60247335 | 0.58057248867732 | 0.000000000437946 | 0.00183688 |

| 23 | 8,388,608 | 0.580572080882894 | 0.000000269019 | 0.60240118 | 0.58057248847340 | −0.000000000203920 | −0.00171060 |

| 24 | 16,777,216 | 0.580572242938665 | 0.000000162056 | 0.60239474 | 0.58057248846243 | −0.000000000010969 | −0.00018403 |

| 25 | 33,554,432 | 0.580572340562639 | 0.000000097624 | 0.60240973 | 0.58057248847781 | 0.000000000015373 | 0.00051584 |

| 26 | 67,108,864 | 0.580572399372356 | 0.000000058810 | 0.60241061 | 0.58057248847835 | 0.000000000000542 | 0.00003640 |

| 27 | 134,217,728 | 0.580572434800094 | 0.000000035428 | 0.60241300 | 0.58057248847924 | 0.000000000000888 | 0.00011919 |

| 28 | 268,435,456 | 0.580572456142390 | 0.000000021342 | 0.60241766 | 0.58057248848028 | 0.000000000001046 | 0.00028071 |

This table resembles those in the 2005 essay, columns having meanings as follows.

More on the eighth column. The absolute differences between consecutive estimates of the limit are a (mostly) decreasing proportion of 2−i. Let’s take them at their largest: assume that they are all positive, and that they are all equal to 2−i. This assumes to unity the coefficient which is already <10−3, and generally of decreasing magnitude, with non-constant sign. Then these assumed future changes, over all not-yet-computed rows, total only 2(−nmax). Despite these overestimates of the possible error, this total is much smaller than the gap between 7⁄12 and the best estimate of the limit.

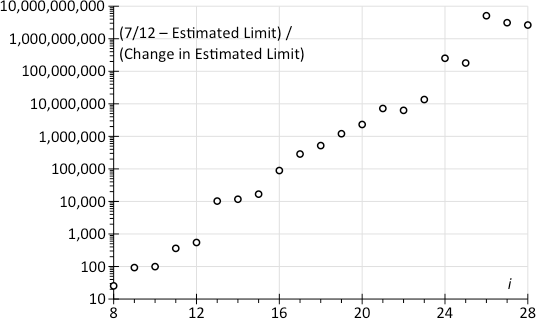

As an alternative, let us assume that the changes in the estimate of the limit are happening pseudo-randomly, changes being centred on 0, and with standard deviation something the absolute value of the change in the estimate of the limit. (It doesn’t matter if this doesn’t hold for all rows: for some rows suffices.) Also assume that this will diminish by only a factor of 2 with each doubling of n, even though the eighth column suggests that the diminishment is slightly faster. Hence, summed over all future rows, the standard deviation of remaining distance of travel is of a similar order of magnitude to this most recent change. The chart on the right shows the distance to 7⁄12 as a multiple of this assumed σ. And behold! The distance is a huge and increasing number of standard deviations. (A one-billion standard deviation move happens, in a normal world, one time in ≈102×1018.) So, relative to the distance that needs to be travelled the changes in the estimated limit are just too small and diminishing too fast: it just isn’t happening.

Note that, for i ≥12, (7⁄12−Estimated limit) ≈ 0.002761, so this chart quickly becomes proportional to the reciprocal of the change in the estimated limit. In some sense, the whole point is the immobility of (7⁄12−Estimated limit) relative to the magnitude of changes in EVn(5,4).

When executing the 2005 version of the code, memory was a slighter tighter constraint than CPU time. This problem was fixable, as then acknowledged:

It is possible to rewrite the program such that the memory usage is linear in the widest gap between the red and grey lines (rather than being linear in n), albeit at the price of a loss of readability. This recoding has not yet been attempted.

This problem has been resolved in the new code version, reducing memory usage by a large factor. The following table shows results for n = 2i.

| i | n = 2i | EVn(0,0) | Diff EV | Ratio Diff EV | Estimated limit = EV + Diff / (1⁄Ratio − 1) | Approx max j | Approx t at which j maximal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 0.770833333333333 | |||||

| 2 | 4 | 0.779947916666666 | 0.009114583333 | ||||

| 3 | 8 | 0.785247657412574 | 0.005299740746 | 0.58145727 | 0.79261028151309 | ||

| 4 | 16 | 0.788190898971545 | 0.002943241559 | 0.55535576 | 0.79186697529802 | ||

| 5 | 32 | 0.790023224424476 | 0.001832325453 | 0.62255354 | 0.79304542974422 | ||

| 6 | 64 | 0.791196842160634 | 0.001173617736 | 0.64050725 | 0.79328787366908 | ||

| 7 | 128 | 0.791897537079360 | 0.000700694919 | 0.59703845 | 0.79293570515041 | ||

| 8 | 256 | 0.792318224291505 | 0.000420687212 | 0.60038570 | 0.79295027021847 | ||

| 9 | 512 | 0.792570438324007 | 0.000252214033 | 0.59952864 | 0.79294801722604 | ||

| 10 | 1,024 | 0.792722493847599 | 0.000152055524 | 0.60288289 | 0.79295333676356 | ||

| 11 | 2,048 | 0.792814414356913 | 0.000091920509 | 0.60451937 | 0.79295492118365 | ||

| 12 | 4,096 | 0.792869752675300 | 0.000055338318 | 0.60202363 | 0.79295346361236 | ||

| 13 | 8,192 | 0.792903056616781 | 0.000033303941 | 0.60182424 | 0.79295339398384 | ||

| 14 | 16,384 | 0.792923109615955 | 0.000020052999 | 0.60212090 | 0.79295345634652 | ||

| 15 | 32,768 | 0.792935195956992 | 0.000012086341 | 0.60271987 | 0.79295353233307 | ||

| 16 | 65,536 | 0.792942476379465 | 0.000007280422 | 0.60236778 | 0.79295350539518 | ||

| 17 | 131,072 | 0.792946862428220 | 0.000004386049 | 0.60244426 | 0.79295350891743 | ||

| 18 | 262,144 | 0.792949504079600 | 0.000002641651 | 0.60228500 | 0.79295350449952 | ||

| 19 | 524,288 | 0.792951095314407 | 0.000001591235 | 0.60236367 | 0.79295350581352 | ||

| 20 | 1,048,576 | 0.792952053932079 | 0.000000958618 | 0.60243634 | 0.79295350654503 | ||

| 21 | 2,097,152 | 0.792952631391198 | 0.000000577459 | 0.60238731 | 0.79295350624769 | ||

| 22 | 4,194,304 | 0.792952979294206 | 0.000000347903 | 0.60247210 | 0.79295350655746 | ||

| 23 | 8,388,608 | 0.792953188872027 | 0.000000209578 | 0.60240302 | 0.79295350640540 | 25689 | |

| 24 | 16,777,216 | 0.792953315120851 | 0.000000126249 | 0.60239592 | 0.79295350639599 | 35349 | 3×105 |

| 25 | 33,554,432 | 0.792953391174430 | 0.000000076054 | 0.60241019 | 0.79295350640739 | 48571 | 6×105 |

| 26 | 67,108,864 | 0.792953436989929 | 0.000000045815 | 0.60241083 | 0.79295350640770 | 66624 | 14×105 |

| 27 | 134,217,728 | 0.792953464589786 | 0.000000027600 | 0.60241310 | 0.79295350640835 | 91212 | 30×105 |

| 28 | 268,435,456 | 0.792953481216427 | 0.000000016627 | 0.60241767 | 0.79295350640915 | 124599 | 646×104 |

The first six columns have meaning similar to those in the h=5 t=3 table.

These columns might be of interest to those attempting further optimisations of the code.

Alas the results have not improved the estimate of the expected value of the whole game. The author also suspects that the accuracy of the C double might be insufficient, or nearly so.

With five heads and three tails, stop, thereby scoring 0.625. Choosing to continue lowers the expected payoff to 0.62361957757…, with the next digit probably being close to ‘3’.

Julian D. A. Wiseman

September 2010

In January 2012 this page was cited (albeit with a punctuation problem in the URL): Olle Häggström and Johan Wästlund, ‘Rigorous computer analysis of the Chow-Robbins game’, arXiv:1201.0626v1 leading to PDF.

| Main index | Top | About J. D. A. Wiseman |