| Main index | Financial Markets index | About author |

Julian D. A. Wiseman

Abstract: the Lɪʙᴏʀ problem could have been fixed by making Lɪʙᴏʀ and like derivatives phyiscally delivered. This was generally, and wrongly, thought impossible.

Publication history: only at www.jdawiseman.com/papers/finmkts/Physically_delivered_Libor.html. Usual disclaimer and copyright terms apply.

Contents: • Introduction; • High-level overview; • The old Certificate of Deposit future; • The new futures contract (Investment-grade players, Remove those with the weakest ratings, Remove those unacceptable to investors, Remove those that go bust, Result, Pre-deliveries); • Lehman Brothers; • Uses (Interest-rate swaps, Floating-Rate Notes); • Summary; • Why it didn’t sell; • Afterwords.

As of late 2019, financial regulators have decided to replace the Lɪʙᴏʀ and Lɪʙᴏʀ-like fixings with something based on an overnight rate. These plans are far advanced.

Back in 2013–’16, I had developed and was advocating a different solution, which was to make all Lɪʙᴏʀ (and Euribor, Stibor, etc) derivatives physically delivered. I thought and still think it the better solution, but the authorities have chosen a different path and so this now won’t happen. Nonetheless, it might be of interest, so is explained here.

The plan was ambitious, and had two major parts.

There was to be a new type of futures contract listed. The new future was to be physically delivered, the underlying being Certificates of Deposit of major banks. This new design had rules very different from that of other deliverable futures (more below), such that the names delivered would be more like median-to-deliver than cheapest-to-deliver. These rules were designed to be robust to many different problems and mischiefs, and did not use any observations of market prices.

Second, assume that in some major currencies such delivered futures exist and are active. These futures could become the underlying for swaps. That is, swaps would be physically delivered into these futures. A few major banks could then do a deal amongst themselves: about a year ahead of each swap fixing, the fixing would be exchanged for the futures contracts either side. Thus those fixings would be ‘delivered’ into futures, which would be delivered into CDs. Obviously, once so tested, other players could adhere to the deal, and derivatives could be deʟɪʙᴏʀised. Because the deal affected fixings up to a year ahead, it would not have de facto long-term lock-in. It would be possible to change it or to scrap it.

Lɪʙᴏʀ derivatives are cash-settled. They settle against an observation of a market price. And whenever there is a change of risk at an observed price, there is an incentive to manipulate the observation. Which is why regulators like physical delivery: it removes the incentive to lie.

And for a future to replace Lɪʙᴏʀ, the natural underlying is Certificates of Deposit (‘CDs’).

But in the early 1980s there were futures with underlyings of CDs issued by the money-centre banks of the era. That worked well, until one of the ten banks whose CDs were deliverable, Continental Illinois, started going bust. CDs issued by Continental Illinois became the cheapest-to-deliver, and Continental Illinois shorted the contract for the purpose of delivering its own CDs and thereby raising funds. The contract’s price became a function of the expected Continental-Illinois recovery rate.

Which is why liquidity moved to the futures settling against 100−Lɪʙᴏʀ.

Compare this to other futures contracts. There are several grades of wheat deliverable into the wheat future. These grades have well-correlated prices: if the price of Red Winter #2 is increasing (or collapsing), then the same will be true of Dark Northern Spring #1. And big moves will be in the same direction and of a similar-ish size, even if not precisely 1-to-1. Likewise, if the yield of a government’s 10-year bond has risen a lot, then the yield of the 8-year bond will also have risen. Maybe a bit more, maybe a bit less, but for large moves the direction will be the same, and the ratio of the size of moves approximately estimatable. So the future, whichever underlying is likely to be delivered, is a functional hedge for the other underlyings. But this isn’t true for bank credit. The price of Lehman debt could be collapsing as that of J. P. Morgan is rallying: price changes really can be huge and in opposite directions. So standard delivery rules wouldn’t work for a bank-debt future.

The answer really needs physical delivery (to remove regulator’s fear of cash settlement’s incentive to lie), but without the cheapest-to-deliver problem (otherwise the future represents the worst bank, not a typical bank).

The answer is a futures contract, again with an underlying of Certificates of Deposit, but with fundamentally new delivery rules. The new rules fix the CTD problem; work in a manner allowing issuers and investors to plan ahead; block many kinds of mischief; and yet do not use any observations of market prices.

The CDs delivered will be those issued by ordinary middle-of-the-pack banks that aren’t in trouble, rather resembling the middle quartiles of a Lɪʙᴏʀ panel, so priced and behaving like Lɪʙᴏʀ.

But achieving that surface simplicity requires some work.

Obviously such a futures contract requires a full legal specification. That was written: seventeen thousand words of clear elegant English, plus another nine thousand words of footnotes to explain to an exchange’s lawyer what mischiefs were being blocked. This web page is not that document; this web page is an explanation and a summary. Indeed, regulators were told that the formal specification had been written assuming that the banks, the investors, the central banks, the regulators, and some but not all exchange staff, were all corrupt crooks, to all of which the specification was robust. Regulators, with Lɪʙᴏʀ trials on the horizon, claimed to like the robustness and paranoia; but upon reflection maybe flattery would have been better salesmanship.

The deliverables were unsecured non-subordinated CDs of the appropriate tenor (3- or 6-month), in the appropriate currency, issued by a bank. But which banks’ CDs were to be deliverable? This is the novel part, and is decided by a multi-stage process which starts five months before the third-Wednesday delivery.

Five months before delivery, the exchange makes the ‘Preliminary List’ of issuers. These are: banks; widely accepted frequent issuers in good size of relevant-currency CDs; and investment grade. Rephrased, they are the investment-grade issuers that are generally acceptable to investors. The names on the Preliminary List might be deliverable, but typically not all will be. (And if there are only ≤7 investment-grade issuers, then there is a waterfall of weakening of the eligibility standard.) For example, in £ the Preliminary List would have had about 35 issuers. (Indeed, the contract specification was written with two currencies in mind: US dollars, and Turkish lira. Because if it works in those two, it would work in currencies such as GBP even if markets were being unusual.)

Twice, six weeks before delivery, and three business days before, the exchange computes the median of the ratings of the issuers on the Preliminary List (there is a formula for averaging the ratings of the different agencies). From the lesser of these two medians one notch is subtracted (so single-A1 becomes single-A2). That is the threshold. The Delivery List is then the Preliminary List without the banks worse than the threshold.

Why two measurements of the median? Assume measured only once, early, and all banks are A1, so the threshold is A2. But what if, soon after, all banks were downgraded two notches to A3: then there would be no deliverables — bad! So assume measured only once, late. Then banks couldn’t plan: an A1 bank might expect to be deliverable, but if all others were hugely upgraded, might not be. Measuring twice allows banks to plan (if first measurement A1, then any banks remaining ≥A2 will be on the Delivery List); and also ensures that at least half of the Preliminary List will be on the Delivery List.

It used to be that investors could trust rating agencies: “we’ll buy anything rated double-A that yields gov’t + 50bp”. Not any more: neither their regulators nor their customers allow that. So longs must also have some independent control over what they might buy.

At the end of a contract’s life, just after trading stops, both longs and shorts submit some information.

Longs can ‘veto’ up to one eleventh of the banks on the Delivery List (so 2 out of 27, or 3 out of 28). But each veto costs 25bp. That is, the delivery yield is lowered by 25bp, hurting the long, but helping the short to whom this lot is assigned. (Why an eleventh? An odd denominator means there’s no need to choose which way to round exact halves; and an eleventh, rather than a ninth or thirteenth, unscientifically seemed to be about correct.)

Shorts can ‘hope’. Hope? Shorts submit a list of names that it would be convenient to deliver. Such hopes might be accommodated, and might not. Presumably almost all hopes would be self-hopes: Barclays hoping to deliver CDs issued by Barclays; J. P. Morgan hoping to deliver J. P. Morgan; Danske hoping Danske; etc.

Then longs and shorts are assigned to each other, in the manner that maximises the number of shorts for which a hoped name has not been vetoed.

It could be that some shorts are unassignable. It could be that Lehman hoped Lehman, and all longs vetoed Lehman. In that case those lots are torn up: the Lehman shorts are cancelled, as is the appropriate fraction of longs.

Nearly there: one more veto. If an issuer goes bust before delivery, that bust issuer is automatically vetoed.

The result is that the deliverable CDs will be issued by ordinary middle-of-the-pack banks that aren’t in trouble, rather resembling the middle quartiles of a Lɪʙᴏʀ panel. The new design of future would behave like a physically-delivered Lɪʙᴏʀ: no incentive to lie, rubbish banks not being deliverable, so priced and behaving like Lɪʙᴏʀ.

For example, in £, as of 2016, the median was single A1, so the threshold would have been A2. The lowest-rated deliverables would have been SocGén, BPCE, Crédit Ag., Danske, Barclays, and the Coventry Building Society. Indeed, 27 of the 35 banks had a rating ≥A2; and there were sixteen banks with a rating within one notch of the CTDs. Hence there were many deliverables, none of whom would have had market power.

Non-CTD banks, and indeed some CTD banks, might pre-deliver. That is, before the end of trading, they would ‘Exchange for Physical’. Consider a hypothetical discussion between a much better name, such as Bank of New York Mellon, and a broker: “Have you any longs who would EfP 3-month £ with BoNYM, three or four days longer than three months, at contracts minus twenty bp?” It’s likely that many deliveries would actually be EfP pre-deliveries. Nonetheless, the delivery rules are essential for determining the correct price.

It must be asked: would Lehman Brothers’ CDs have been delivered in September 2008? Absolutely not, for three reasons, any one of which would have sufficed.

Lehman might have been in the Preliminary List, sure, if it were an active issuer of CDs in that currency. But in 2008 most relevant banks were Aa1 or Aa2, so the threshold would have been Aa2 or Aa3. But in that era Lehman had been single-A1, and that summer had been downgraded to single-A2. Lehman would have been too far below the median rating of the Preliminary List to have been in the Delivery List.

But even if it had been in the Delivery List, on the Monday morning the exchange would have vetoed it, at no cost to longs, because it was bankrupt.

And if by Monday it was nearly but not quite bust, or if there had been a bank holiday such that longs had to decide this on Friday rather than Monday, then longs would have vetoed it, willingly paying that 25bp cost. For a three-month contract, only 0.06¼ per 100.00 principal.

So longs were triple-protected against being delivered Lehman paper on the third Wednesday of September 2008, and any one of those three protections would have been enough.

These protections remove the CTD problem.

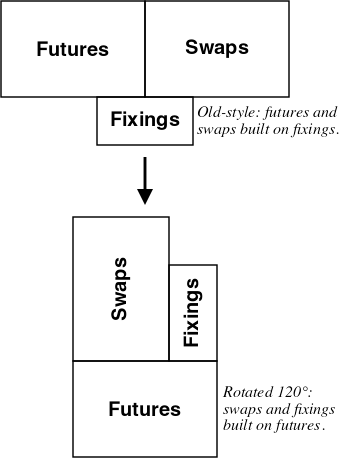

That replaces Lɪʙᴏʀ in the context of futures. But the main use of Lɪʙᴏʀ is in interest-rate swaps. Currently swaps are built on a numerical fixing, but swaps can be built on a futures contract. Even existing swaps could have been deʟɪʙᴏʀised.

There would have been a multilateral ISDA protocol. For contracts between those adhering, usage of Lɪʙᴏʀ / Euribor / Tɪʙᴏʀ / Stibor / etc would have been switched to the new futures. Initially, a few players would join; over time, more.

How would it have worked? As before, this summarises.

For example, assume that it is now March 2020, and that for settlement on 24th March 2021 there is a fixing in an outstanding £1bn swap. That fixing, one year in advance, is switched for futures. The receiver of the swap acquires 800 × Mar2021 futures and 200 × Apr2021 futures (as Wed 24th Mar 2021 is a fifth the way between the third-Wednesday delivery dates, and assuming the future has a nominal size of £1,000,000). The payer of the swap would sell the same quantities of futures. The futures transactions happen at the previous closing price, and same-risk one-period swaps are executed in the opposite direction, at a price of the weighted average of the futures’ closing yields. Voilà: Lɪʙᴏʀ exposure deleted, and replaced with physically delivered futures.

So swaps, even the $300 trillion of outstanding swaps, could have been deʟɪʙᴏʀised, and deʟɪʙᴏʀised without players committing to a particular mechanism for longer than a rolling year. Which is an important advantage: any new system can go wrong, as Lɪʙᴏʀ has. But this new protocol has a maximum commitment of one year: if switched off — the switch presumably being controlled by each currency’s central bank — within a year it would be gone. That absence of lock-in is a good thing.

Can Floating-Rate Notes be deʟɪʙᴏʀised? FRNs have many holders, so renegotiation of existing FRNs would be effectively impossible, and a unilateral imposition of a new index would be a technical default. Hence existing Lɪʙᴏʀ-referencing FRNs must continue to reference the same fixing. Changing them requires that Lɪʙᴏʀ itself point to this mechanism, which is possible but not necessary for the other benefits.

New FRNs could reference the future. Consider a new FRN paying coupons on third Wednesdays. The FRN’s coupon could be linked to the price of the future. Obviously a single observation could be manipulated, especially if it were the EDSP. So not that. Instead the exchange should calculate the average price over two weeks, ending about three weeks before the end of trading. For each minute of each of these daytime trading sessions, the exchange records the median traded price. Each day there is an average price, being a trimmed mean of these one-minute medians; the final score being a simple mean of these ten daily trimmed means.

(Footnote. This layering does have a purpose. A small currency, such as Norwegian krone, would likely not have enough trading action to support many trading hours per day. So, trading could be in Rings — as used on the London Metal Exchange — the NOK CD future perhaps being open for twenty minutes a day, perhaps the five minutes from each of 08:05, 10:05, 13:05 and 15:05. Suppose that there’s been big news in this market, and trading volumes are huge, and the yield very different. The exchange wants to lengthen the opening hours; the exchange wants there to be more trading minutes per day. If the final score were an average of all trades, or an average of each minute’s score, then a change in the trading hours would increase the weighting of prices from the later days, and so change the expected value of the fixing. But an average of the daily averages allows the exchange the flexibility to change trading times without any ex ante expected change in the FRN fixing. The specifications had multiple such subtleties.)

This average is over a period of time near the end of a contract’s trading, but not so near that those unable to make or take delivery are prevented from participating. And 10 business days × 8½ trading hours per day × 60 minutes per hour = 5,100 observations. An attempt to manipulate a $|€|£ 10bn fixing would have average ‘firepower’ of less than two lots per observation (assuming the future’s notional size is one million). Even an unprecedently huge 100bn fixing would have only 19 lots per observation. So this average would be robust.

FRN coupons not on third Wednesdays would be interpolated between these pre-expiry averages of adjacent months. Even though this would be an interpolation between prices of different things observed at different times, it would retain the original Lɪʙᴏʀesque meaning, and would be fully hedgeable with futures.

Could this new ‘fixing’ be used for swaps? In theory, perhaps. But regulators would surely prefer the no-change-of-risk exchange for futures, as that makes manipulation purposeless.

These things combine nicely: swaps (the fixings of which become futures) can, as now, precisely hedge FRNs, the futures being unwound during the two weeks over which the average price of the future is calculated.

Regulators believed that Lɪʙᴏʀ’s problems could not be fixed. But Lɪʙᴏʀ could have been replaced with a new futures contract with fundamentally new delivery rules, such that deliveries resemble median-to-deliver rather than cheapest-to-deliver. That contract would have given banks a new source of term funds, and could have been an underlying for swaps and a coupon rate for FRNs.

Rephrased, a measurement of the cost of term unsecured non-subordinated borrowing of a middle-of-the-pack bank could have been replaced with actual term unsecured non-subordinated borrowing of a middle-of-the-pack bank. There could have been no change in meaning.

And the exchange that listed it could have had a massively successful futures contract, and would have been at the centre of all fixed-income markets, with all the associated opportunities.

Many failures have many possible causes, and it is not always possible to know for sure which hurt and which didn’t. For this, I see five reasons that it didn’t sell.

Exchanges’ lack of imagination. One exchange said, explicitly, that it is and wishes to be a boring utility: water has to come out of the tap; the exchange has to be open. (This doesn’t necessarily mean that individuals at exchanges lack imagination; it means that the corporate culture works against it.) It was argued that the 3-month Lɪʙᴏʀ contracts were 22% of trades on the CME, which had a market cap of $40bn; so the USD contract alone was worth something like $9bn; to which add € + £ + Swiss + CAD + AUD + NZD + Scandis + a tail of emerging markets; each of which would have much more volume because of the feed-in from swap fixings. To no avail.

Regulatory decision cowardice. Regulators loved physical delivery. A typical comment loved the delivery, expressed great interest, and “please do keep us informed”.

My reply to that: “Can’t get traction at exchanges. Would you, the regulator, be willing to contact somebody senior at exchanges X and Y, and say something like: ‘We understand that you have been speaking to Wiseman about a physically-delivered Lɪʙᴏʀ. We (regulator) do not fully understand it, and so do not know whether it will work. If you (the exchange) have interesting reasoning about this proposed solution, we would very much like to hear it.’ Please?”

All of which was completely true. The object was to have senior people at exchanges give it some focus. Recall that at the time banks were being fined billions and individuals were being arrested: everybody wanted to be seen to obey orders and not more than that, so all asked “What do the regulators say?” But the regulators, despite wanting the problem fixed, did not want to be seen to own or control the solution.

Later, in July 2017, the CEO of the Financial Conduct Authority gave a speech, warning that Lɪʙᴏʀ might not last past 2021. Yet still regulators describe the reform as “market-led” (e.g., google leads to Sep 2018 letter from BoE and FCA, ¶2; mid 2019 FCA notice; late 2019 FCA notice, etc). And when market participants have argued for using a fixing of OIS, regulators have quietly made their disapproval known.

It had to be regulator-led, and indeed is regulator-led. Had that been acknowledged, a better solution could have been chosen. Instead Lɪʙᴏʀ is to be converted to compounded overnight; banks thereby pushed to funding overnight not term; so the banking system is less stable.

The plan was big. There was a one-step-at-a-time route through, but big success required multiple parts to come good, which in turn required explicit regulatory enthusiasm. Maybe too much had to come good for this to be Lɪʙᴏʀ’s replacement.

Patent application but not an actual patent. I had applied for a patent (US Patent and Trademark Office, google). The application had passed the novelty test. But the application had been rejected “because the claimed invention is directed to non-statutory subject matter” (§101). The USPTO was then rejecting most patent applications for things that looked like business processes, because of the Alice ruling.

But it was clearly patentable (says the inventor who had a financial interest in it being so). Board games are patentable; what is patented is not whether the pieces are made of metal or plastic; what is patented are the rules and game play. This is just the same: rules and game play, but of a futures contract rather than a board game. The US Constitution allows patents to promote “the Progress of … useful Arts”: surely making interest-rate fixings honest is a more useful art than is a board game! I didn’t have the money to fight through the necessary chain of appeals, so, when attempting to sell it, didn’t have an actual patent.

The application has since been abandoned.

Failure of salesmanship. The previous four problems were important, but should not have been insuperable. But were not supered: there must also have been, mea culpa, a failure of salesmanship.

— Julian D. A. Wiseman

London, December 2019

Derived from work 2013–16

www.jdawiseman.com

If commenting publicly about this page, please tag with #DeliveredLibor (using ASCII rather than small caps). Searches: google; twitter; and LinkedIn.

Replies to such comment might, and might not, appear here.

To my elder daughter I explained quite how big the royalties might have been (1¢ per trade, times 10 million trades a business day, would have been, err, lots). She said — and I thought that her playfulness was delicious — “I could have had a walk-in closet. I could have had a walk-in closet with an escalator. I could have had a walk-in closet with an escalator leading to soft pretzel bar.” Father admitted to not liking pretzels. “Nor do I”, said she, “but I just love the idea that I could walk into my walk-in closet, in my pyjamas, and, at the top of the escalator, get a soft pretzel.” Having said that this wasn’t what I had envisaged, she replied “Then perhaps you didn’t deserve to sell it.” Soft pretzels, eh: who knew?

(Later, reading this, she added “Bagels would have been better.”)

| Main index | Top | About author |